What is Alzheimer’s disease?

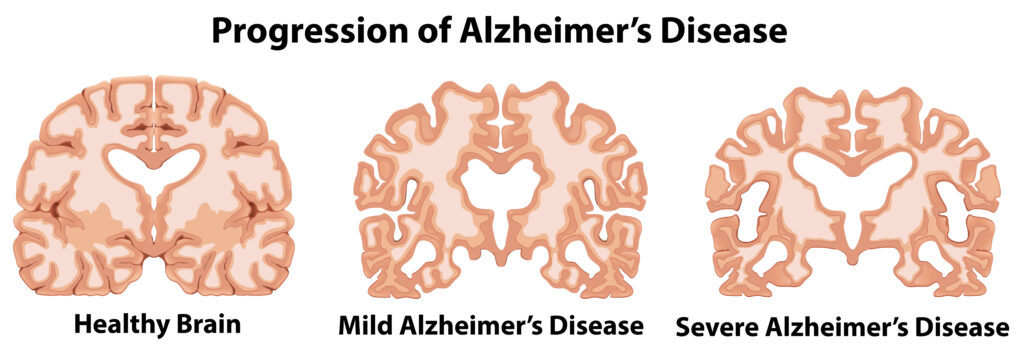

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia worldwide accounting for 60-70% of cases. It is a neurodegenerative disorder which means that it affect the health and function of the brain resulting in cognitive impairment. Individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease experience a progressive decline in memory, learning, language and comprehension1. The primary risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is ageing with approximately 6.2 million Americans aged 65 and older living with Alzheimer’s disease in 2021. The cases of Alzheimer’s disease are exponentially increasing due to individuals living longer and therefore we see the manifestation of these age-related diseases. Alzheimer’s disease is not only an individual or family issue but is also a societal and healthcare concern2. Although Alzheimer’s disease mostly affects the elderly, it is not a normal part of ageing. With normal ageing there is a shrinkage of nerve cells which affects their function (i.e., age-related forgetfulness), however, the function is not completely lost; individuals can undertake everyday tasks. Conversely, with Alzheimer’s disease the function is progressively lost which affects everyday tasks (e.g., getting dressed, making breakfast etc.).

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by the accumulation of toxic proteins in the brain. These proteins include amyloid-β and tau. Their build up results in the loss of communication between neurons (via communicating junctions called synapses) leading to the death of the neurons starting at the hippocampus (the region of the brain that is responsible for learning and memory) and ultimately global brain shrinkage. It is an insidious disease as the symptoms of cognitive decline occur some 10 or so years later than the initial changes in the brain cells3.

Familial and Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is split into two categories: familial cases and sporadic cases. The familial form is rare, accounting for approximately 5% of the Alzheimer’s disease cases and is caused by mutations in three important genes: [amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, presenilin1 (PSEN1) gene and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) gene]. On the other hand, the sporadic form is more prevalent, representing 95% of the total cases. It is more multifactorial and has both genetic and environmental contributions. Studies have shown that approximately 30% of sporadic cases are linked to the APOE gene. Although much research has been conducted in understanding the nature of Alzheimer’s disease, a lot is still unknown about the exact causes of the sporadic form of Alzheimer’s disease4,5,6.

Environmental Factors: The Triad of Neuro-threats

As mentioned previously, the prominent form of Alzheimer’s disease is the sporadic form. There is a strong link with how environmental factors and pre-existing conditions affect the manifestation of the disease. For example, individuals who have been involved in car crashes resulting in traumatic brain injury (TBI) or mild-repeated TBI such as high impact sports like American football have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)7,8. Additionally, Dr Dale Bredesen mentioned in his book, The End of Alzheimer’s, that there are three specific factors that threaten the health of the brain: inflammation, shortage of brain supporting molecules and exposure to toxic substances. He mentions that the brain’s response to these threats results in Alzheimer’s disease9.

Inflammation

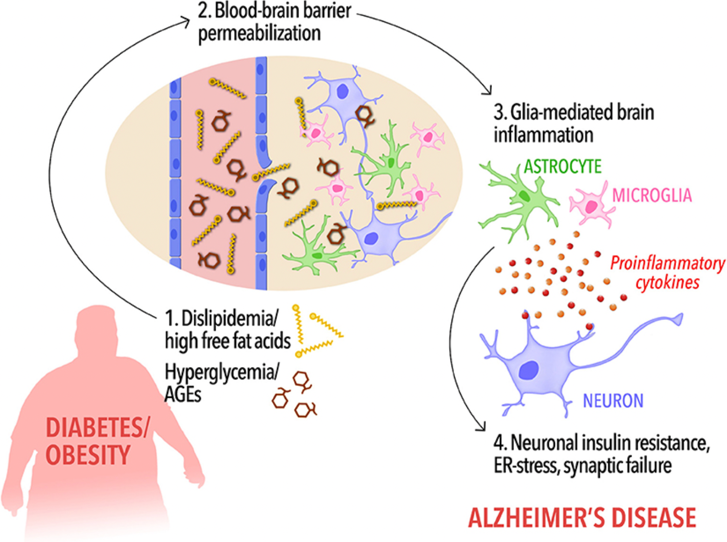

Inflammation is a normal biological response to what the body deems as an invasion or attack. This attack can be by a pathogen such as the Ebola Virus or by non-pathogenic agents such as trans fats (e.g., from fries or chips) or proteins that have been damaged by high levels of glucose. The body responds by activating the immune system to mobilise white blood cells to clear away the pathogen9. This results in an inflammatory response (e.g., the redness that surrounds a fresh cut on the arm) that ends when the threat has been dealt with. However, when we continuously consume high-sugar foods and trans fats for example, the inflammatory response will always be activated. A component of the inflammatory response is the production of

amyloid-β (which forms the plaques found in Alzheimer’s disease). This will then lead to an accumulation of this protein leading to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease in later life. Moreover, a high-sugar diet can lead to hyperglycemia (high levels of glucose in the bloodstream). The body tries to lower the excessive levels by increasing the production of insulin. However, in response to extremely high levels of insulin the body turns down its response to insulin leading to insulin resistance9. Tragically, high levels of insulin is linked to Alzheimer’s disease and amyloid-β accumulation. When insulin is successful in lowering the glucose levels, the body will need to degrade it in order to prevent insulin from lowering the glucose levels too much. This is done by the Insulin Degrading Enzyme (IDE). However, IDE also degrades amyloid-β, but it cannot degrade both insulin and amyloid-β at the same time. Therefore, high levels of insulin (due to high levels of glucose from a high-sugar diet) will halt the removal of amyloid-β which increases Alzheimer’s disease progression9,10.

Exposure to toxic substances

Interestingly, when the body is exposed to toxins, amyloid-β acts like an antivenin by binding to toxins such as mercury (e.g., from king mackerel fish) and biotoxins (e.g., mycotoxins from mould) and inactivate them which prevents them from damaging neurons9,11. Constant exposure to toxins can lead to a build-up of amyloid-β which will then cause the formation of amyloid plaques, characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease9.

Shortage of brain-supporting molecules

Shortage of brain-supporting molecules and inflammation are linked to metabolism which is influenced by diet, exercise, stress and our genes. Our nutrition and activity level influences our brain health which influences our overall health9. A healthy brain needs several neuron and synapse supporting factors/molecules. An example of one of these factors is the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The levels of BDNF are increased through exercise, hormones such as testosterone and nutrients such as vitamin D. BDNF increases the growth of neurons and synapse formation which can combat the effects of toxic amyloid-β and rescue neurons from cell death9.

Final thoughts

In summary, living a healthy and balanced lifestyle can help to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. These healthy choices can include opting for nutritious and balanced food, getting adequate rest, and increasing daily movement whether through exercising, taking your dog for a walk, parking further away from your workplace to increase your daily step count or following along to a fun Zumba class on YouTube! Another crucial factor that we should consider is lowering our stress levels, which can be super challenging as we live in a high-stress society. But managing our stress levels can help us reduce the risk of various health issues. This is because being stressed leads to the release of the hormone cortisol which has been shown to have deleterious effects on the body especially the brain. Stress is also closely linked to conditions such as depression and anxiety, which have also been suggested as factors that could increase the risk of dementia. If you need assistance with managing your stress there are various resources that can be of help such as licensed therapists, meditation apps and local mental health services.

References

- Who.int (2021).at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia (2021).at https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- Toepper, M. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 57, 331-352 (2017).

- Piaceri, I., Nacmias, B. & Sorbi, S. Frontiers in Bioscience E5, 167-177 (2013).

- Dorszewska, J., Prendecki, M., Oczkowska, A., Dezor, M. & Kozubski, W. Current Alzheimer Research 13, 952-963 (2016).

- Barber, R. Scientifica 2012, 1-14 (2012).

- Nordström, A. & Nordström, P. PLOS Medicine 15, e1002496 (2018).

- Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia (2021).at https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/related_conditions/traumatic-brain-injury

- Bredesen, D. (Penguin Publishing Group: 2017).

- Farris, W. et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100, 4162-4167 (2003).

- Brothers, H., Gosztyla, M. & Robinson, S. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 10, (2018).